Is CAA a ‘blessing in disguise’ for the long-standing issue of Chakma-Hajong?

With

Union Minister Kiren Rijiju's recent statement on reallocating Chakma-Hajong to

Assam, the long-standing issue of Chakma-Hajong has again come to the fore.

Rijiju’s stance emphasizes the challenges faced by the 67,000 Chakma-Hajong in Arunachal Pradesh debarred from obtaining citizenship in the State citing the non-applicability of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). He proposed relocation to Assam as a solution highlighting the benefits of CAA for Arunachal Pradesh. Further, entitling to a discussion about the re-settlement of the Chamas-Hajong with Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma and also with Union Home Minister Amit Shah to find some land by any means in Assam for their re-settlement.

The Union Minister further gave a statement of CAA being a ‘blessing’ for the Government of Arunachal Pradesh and called out the Chakma Hajong refugees as guests in their State who had been residing for over six decades.

Sarma, on the other hand, opposes any such move and prefers to deal with the matter post-election to avoid political speculation, emphasizing the importance of dialogue and resolution without further upheaval.

This is not the first time the relocation of Chakma Hajong came to the fore. Earlier, on August 15, 2021, Chief Minister Pema Khandu announced in his speech that all illegal immigrant Chakmas would be relocated.

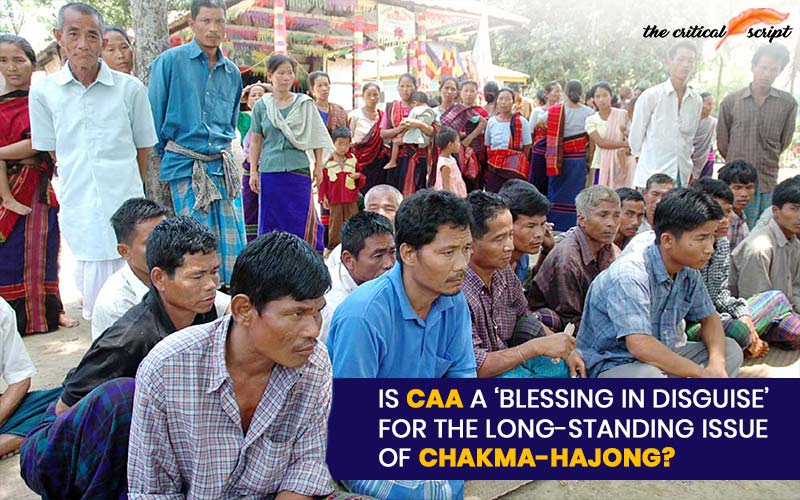

The Chakma Hajong trace their origins to the Chittagong hill Tracts of erstwhile East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. Chakmas, Buddhists, and Hajongs, Hindus, fleeing religious persecution and displacement caused by the Kaptai dam construction in the 1960s, sought refuge in India. Chakmas and Hajongs entered India through the then Lushai Hills district of Assam (now Mizoram). Some remained in the district with the Chakmas that had already been settled. Many Chakmas and Hajong were resettled to the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA), now Arunachal Pradesh, where they face citizenship and land rights challenges.

If we talk about the legal dimensions of the Chakma Hajong their battle for citizenship rights and recognition is still ongoing.

Despite several interventions by the Supreme Court of India, the implementation of rulings favouring the Chakma Hajong has been sluggish, exacerbating their plight and contributing to ongoing uncertainties surrounding their status in Arunachal Pradesh.

For instance, the Supreme Court’s interim order on November 2, 1995, directed the Government of Arunachal Pradesh to ensure that the Chakmas situated in its territory are not ousted by any coercive action, not in accordance with the law. Further, in the landmark case of NHRC vs Arunachal Pradesh (1996), the Supreme Court affirmed the fundamental rights to life and liberty of every citizen, emphasizing the need to protect the Chakma Hajong rights and prevent their eviction from their homes.

In addition, the Delhi High Court’s judgment in 2000 acknowledged that the majority of Chakmas and Hajongs are citizens of India by birth under Section 3(1) of the Citizenship Act of 1955, underscoring the legal basis for their entitlement to fundamental rights guaranteed under the Indian Constitution.

Despite these clear directives from the highest judicial authority, the Government of Arunachal Pradesh failed to fully comply with the court’s orders, leading to continued uncertainty in the Chakmas Hajong communities. Chakma organisations, however, have been demanding citizenship certificates for the Chakma and Hajongs as directed by the Supreme Court in 1996 in its order regarding the NHRC vs Arunachal Pradesh government case.

The recent statement of Union Minister Kiren Rijiju on relocating the Chakmas Hajong to Assam citing the non-applicability of CAA, with the ongoing Lok Sabha polls, seems to be making another attempt to use them as “puppets” for electoral gains.

● On

the one hand, the state government and certain indigenous communities are

adamant about relocating these two communities. In August 2021, the All

Arunachal Pradesh Students' Union (AAPSU) and the state unit of the Nationalist

People Party (NPP) stated to the media that the people of the state would never

accept the Chakma and Hajong refugees. Then NPP President Mutchu Mithi expressed

concern over the growing population of refugees and said that their population

at present is between one and 1.5 lakh, which is much higher than some of the

indigenous tribes of the state. He had said that granting them citizenship

would create a drastic demographic as well as political change in Arunachal

Pradesh.

Chakma and Hajong

refugees continue to be denied basic rights and face threats to their

livelihoods. Moreover, the suspension of residential proof certificates sites

their peril limiting their mobility and access to essential services.

Unlike permanent residence certificates, RPCs are temporary documents issued to persons residing in a particular place. In Arunachal Pradesh, RPCs are issued to members of Chakma and Hajong communities who have yet to be granted Indian citizenship, don’t possess documents like passports and are not included in voter lists. The RPCs help them to pursue higher education in other states and join paramilitary forces.

In conclusion, the Chakma-Hajong issue in Arunachal Pradesh is a complex conundrum with no easy solutions.

Fighting constantly for citizenship rights and fear of getting moved out measures the depth where this long-pending issue needs immediate resolution.

Not for gaining votes but in actual Chakma-Hajong communities who have been settled for almost six decades in Arunachal Pradesh need a balanced approach that respects both their rights and dignity. The resolution needs to have constructive dialogue, ensuring their fate and not making them just a mere puppet on grounds of political morale.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Critical Script or its editor.

Newsletter!!!

Subscribe to our weekly Newsletter and stay tuned.

Related Comments