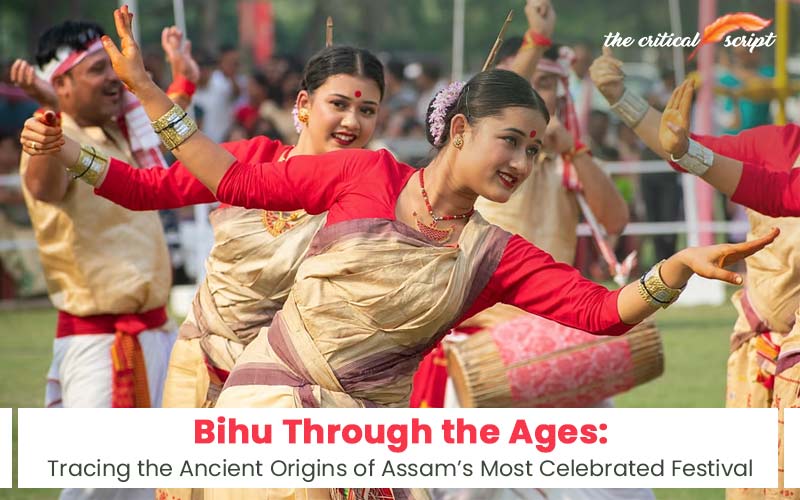

Bihu Through the Ages: Tracing the Ancient Origins of Assam’s Most Celebrated Festival

From tribal fertility

rites to a symbol of Assamese identity, Bihu has evolved over centuries as a

cultural cornerstone rooted in agrarian traditions and seasonal rhythms.

The

festival of Bihu, synonymous today with Assamese pride and unity, has a rich

and complex history that predates written records. Celebrated in three seasonal

forms—Bohag Bihu (Rongali Bihu), Kati Bihu (Kongali Bihu), and Magh Bihu (Bhogali Bihu)—this vibrant

festival encapsulates Assam’s agrarian heritage, fertility worship, and

communal celebration. Though widely popular across caste and class lines today,

the earliest traces of Bihu are found in the pre-Aryan tribal cultures of Assam, particularly among the Deori, Chutiya, Moran, Mishing, Bodo, and

Lalung communities.

One

of the earliest mentions of a festival similar to Bihu comes from the Deori tribe, who celebrated “Bisu”, a New Year and harvest festival

that involved offering prayers to nature deities, community dancing, singing,

and feasting. Scholars suggest that the name “Bihu” evolved from this Deori

term “Bisu,” meaning ‘excessive joy’ or ‘a period of abundance’. Similar

linguistic and ritualistic roots are also observed among the Chutiyas, where spring festivities were

conducted in honor of the agricultural cycle. As per Dr. Birendranath Dutta, a leading authority on Assamese folk

culture, the Bihu dance and Bihu geet likely developed from the open-air,

communal fertility rituals performed by these tribes in pre-literate Assam.

In

terms of seasonal context, Bihu aligns with various other South and Southeast Asian solar new year festivals, such as Songkran in Thailand, Thingyan in Myanmar, Pimai in Laos, and PohelaBoishakh in Bengal, all of which occur in mid-April and are

marked by water rituals, agricultural rites, and communal gatherings. This

suggests a broader Austroasiatic and

Tibeto-Burman cultural continuity, wherein agrarian societies across Asia

celebrated solar transitions as sacred moments of renewal.

The

earliest historical endorsement of Bihu can be traced to the Ahom dynasty, which ruled Assam from

the 13th to 19th centuries. The Ahoms,

originally a Tai-Shan people, assimilated many local customs, and Bihu became

part of the royal tradition during the reign of kings like Suhungmung (1497–1539) and RudraSingha

(1696–1714). Under their patronage, Bihu acquired a more structured public

expression. During the Ahom period,

courtiers and villagers alike participated in Bihu festivities, with Husori teams (groups of Bihu performers)

visiting homes to offer blessings through songs and dances. Notably, the Rang Ghar, constructed by King PramattaSingha in the 18th century near

Sivasagar, served as a venue for Bihu-related performances and sports like

buffalo fights during the Rongali Bihu season. The Tai-Ahom Buranjis (chronicles) and works such as “DeodhaiBuranji” contain references to

seasonal celebrations resembling Bihu, highlighting the fusion of Tai and

tribal traditions.

Sociologist H.K.

Barpujari and historian S.K. Bhuyan both emphasized how Bihu, while rooted in tribal

rituals, played a vital role in the formation of a collective Assamese identity

- especially during the colonial period, when folk festivals became mediums of

cultural assertion. The inclusion of Bihu dances and songs in Assamese

literature, theatre, and eventually the freedom movement, redefined Bihu from a

village-centric festivity to a symbol of state-wide unity and resilience.

Each

form of Bihu continues to reflect a specific agricultural phase - Bohag Bihu welcomes the sowing season

with youthful celebration and courtship songs under the moonlight; Kati Bihu, more solemn in tone, centers

around prayers for the paddy crop’s growth, symbolized by lighting earthen

lamps in the fields; and Magh Bihu

marks the end of the harvest with feasting, the burning of Meji (bonfire), and offerings to ancestors. These customs resonate

with ancient fertility rites observed in various agrarian societies, pointing

to Bihu’s deeply spiritual, seasonal core.

Today,

Bihu is not just a festival - it is an emotion that binds people across

religious, linguistic, and ethnic boundaries in Assam. Whether performed on a

stage in Guwahati or under the moonlight in a distant village, Bihu represents

continuity with the past, the rhythm of nature, and the resilience of

indigenous cultural expressions.

The

enduring popularity of Bihu in the modern era, celebrated in schools, urban

centers, diaspora communities, and even international stages, is a testament to

its organic evolution and adaptability. It stands as a cultural beacon -

reminding us that the soul of Assam lies in its fields, its folk songs, and the

timeless joy of Bihu.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Critical Script or its editor.

Newsletter!!!

Subscribe to our weekly Newsletter and stay tuned.

Related Comments