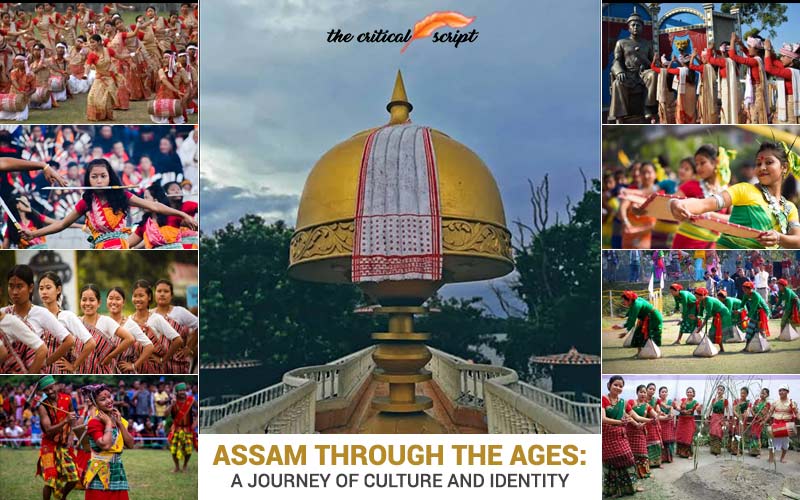

Assam Through the Ages: A Journey of Culture and Identity

The roots of culture in Assam go back almost five thousand years when the first wave of humans, the Austroasiatic people, reached the Brahmaputra valley. They mixed with later immigrant Tibeto-Burman and Indo-Aryan peoples throughout prehistoric times. The last wave of migration was that of the Tai/Shan, who later contributed to shaping Assamese culture and identity. The Ahoms further brought Indo-Aryans such as Assamese Brahmins, Ganaks, and Kayasthas to Assam.

The culture of Assam is

traditionally a hybrid one, developed through the cultural assimilation of

various ethno-cultural groups under different political and economic systems

throughout its history.

According to the epic Mahabharata

and local folklore, the people of Assam (Kiratas) probably lived in a strong

kingdom under the Himalayas in the era before Christ, which led to early

assimilation of various Tibeto-Burman and Austroasiatic ethnic groups on a

greater scale. The typical naming of rivers and the spatial distribution of

related ethno-cultural groups also support this theory.

Later, the western

migrations of Indo-Aryans such as various branches of Irano-Scythians and

Nordics, along with mixed northern Indians (from ancient cultural regions such

as Magadha), enriched the aboriginal culture. Under stronger political and

economic systems, Sanskritisation and Hinduisation intensified and became more

prominent. Such an assimilated culture, therefore, carries many elements of

diverse source cultures, whose exact roots are difficult to trace and remain

subjects of research.

However, in every element

of Assamese culture - language, traditional crafts, performing arts,

festivities, and beliefs - either indigenous elements or indigenous elements in

Sanskritised forms are always present.

It is believed that

Assamese culture developed its roots over 750 years during the era of Kamarupa

in the first millennium AD, marked by the assimilation of the Bodo-Kachari

people with the Aryans. However, this is debatable, as the concept of

"Assam" as an entity did not yet exist. The first 300 years of

Kamarupa were ruled by the Varman dynasty, followed by 250 years under the

Mlechchha dynasty, and 200 years under the Pala dynasty. Records of various

aspects of language, traditional crafts (such as silk, lace, gold, and bronze)

are available in different forms.

When the Tai-Shans entered

the region in 1228 under the leadership of Sukaphaa to establish the Ahom

kingdom, a new chapter of cultural assimilation began, lasting nearly 600

years.

Symbolism is an important

aspect of Assamese culture. Various elements are used to represent beliefs,

feelings, pride, and identity. Symbolism is an ancient cultural practice in

Assam and remains highly significant today. Tamulpan, Xorai, and Gamosa

are three of the most important symbolic elements in Assamese culture.

Tamul-paan (areca nut and betel leaves), or guapan

(with gua from the Bodo-Chutia language), are considered offerings of

devotion, respect, and friendship. This is an ancient tradition rooted in

aboriginal culture and followed since time immemorial.

Xorai, a traditional symbol of Assam, is a crafted

bell-metal object of great respect. It is used as a container while making

respectful offerings. Shaped like an offering tray with a stand at the bottom,

similar to those found in East and Southeast Asia, it can be made with or

without a cover. Traditionally made of bell metal, Xorais are now also made of

brass or silver. Hajo and Sarthebari are the most important centers of

traditional bell-metal and brass crafts, including Xorais.

Xorais are used to offer tamul-paan

(betel nut and leaves) to guests as a gesture of welcome and gratitude. They

are also used for offerings placed in front of the altar (naamghar), as

decorative symbols in functions such as Bihu dances, and as honorary gifts

during felicitations.

The Gamosa is an

article of deep significance to the people of Assam. Literally translated, it

means "something to wipe the body with" (Ga = body, mosa

= to wipe), though interpreting it merely as a body-wiping towel is misleading.

Its original term is Gamcha.

It is usually a white

rectangular piece of cloth with a red border on three sides and red woven

motifs on the fourth. Though commonly used to wipe the body after bathing (a

ritual act of purification), the Gamosa serves many other roles.

A farmer may wear it as a

waistcloth (tongali) or loincloth (suriya). A Bihu dancer wraps

it around the head. It is hung around the neck in prayer halls and was once

draped over the shoulder to signify social status. Guests are welcomed with a

Gamosa and tamul. Elders receive bihuwaan (Gamosas) during Bihu.

It is used to cover altars or scriptures and to place under objects of

reverence.

Thus, the Gamosa truly

symbolizes the life and culture of Assam. Importantly, it is used by people

across religious and ethnic lines.

Parallel to the Gamosa,

various ethnic communities in Assam have their own beautifully woven symbolic

garments with graphic designs. Other traditional symbolic elements are now

preserved in literature, art, sculpture, architecture, or used only for

religious purposes on special occasions.

Every thread of the

Assamese Gamosa carries the heritage of Assamese culture. It is not merely an

accessory but a living testament to Assam’s cultural richness, tradition, and

timeless glory.

Paintings of Assam

Assam’s artistic heritage

is interwoven with myriad expressions that capture the essence of its history,

culture, and spirituality. One of its most captivating art forms is the Assamese

scroll painting, often referred to as Pattua painting, scroll

painting, or pattachitra. These paintings narrate myths, legends,

historical events, and spiritual tales through intricate and vibrant

compositions.

Originating from the heart

of Northeast India, these scrolls reflect the profound influence of

Vaishnavism, particularly the spiritual renaissance led by reformers like SrimantaSankardev.

These artworks not only display creative mastery but also encapsulate the

cultural richness, spiritual depth, and historical narratives of Assam.

The tradition of manuscript

painting flourished with the rise of Neo-Vaishnavism, introduced by the

saint and reformer Sankardev (1449–1568 AD). These manuscripts were created

using locally sourced materials and reached their peak between the 16th and

19th centuries, preserving Assam’s cultural continuity through detailed visual

storytelling.

Tracing even further back,

Assam’s artistic journey begins in antiquity. References to artists and

paintings appear in texts like the Harivamsa and Dwarika-Lila,

derived from the Mahabharata. One such anecdote tells of Chitralekha

of Sonitpura, a renowned painter who sketched Aniruddha, the

grandson of Lord Krishna.

Another reference comes

from Banabhatta’sHarshacharita (7th century AD), which notes that King

Bhaskara of Kamarupa gifted King Harsha of Kanauj "elaborately carved

boxes containing painting panels, brushes, and gourds."

The epic stories of the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Krishna Leela offered a vibrant canvas for artistic expression. The ability of these artists to infuse deep emotion and devotion into their work made these stories accessible to all, marking a profound cultural and spiritual awakening.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Critical Script or its editor.

Newsletter!!!

Subscribe to our weekly Newsletter and stay tuned.

Related Comments