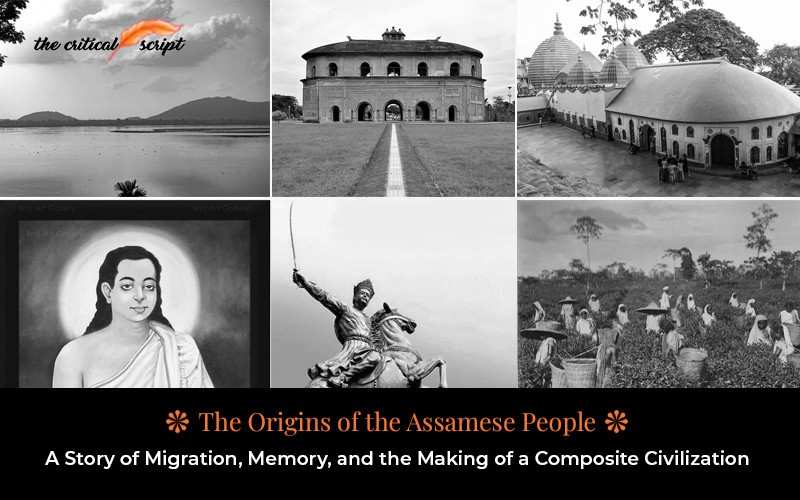

The Origins of the Assamese People A Story of Migration, Memory, and the Making of a Composite Civilization

Introduction: A Land of Confluence

The origins of the Assamese people cannot be traced to a single

tribe, dynasty, or migration. They represent the outcome of thousands of years

of movement, settlement, negotiation, and cultural synthesis in the fertile

Brahmaputra Valley. Assam’s geographical position, nestled between the

Himalayas, the Indo-Gangetic plains, Tibet, Bhutan, Myanmar, and Southeast Asia,

made it one of South Asia’s most dynamic frontier regions.

Rather than a homogeneous race, the Assamese people emerged from

the blending of Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman, Indo-Aryan, and Tai influences.

Their identity was not born overnight; it evolved gradually through state

formation, religious reform, language development, and resistance to external

powers.

This is the story of how a frontier became a homeland.

The Earliest

Inhabitants: Prehistoric Foundations

Archaeological discoveries at Daojali Hading and other sites indicate human habitation in Assam dating back to the Neolithic period (around 2700–1500 BCE). Stone tools, handmade pottery, and evidence of shifting cultivation suggest the presence of early Austroasiatic and later Tibeto-Burman populations.Many contemporary tribal communities of Assam, including the Bodo, Dimasa, Karbi, Mising, Rabha, Tiwa, and Deori, belong to the Tibeto-Burman linguistic family. These groups are considered foundational to Assam’s demographic and cultural formation.

Their agricultural techniques, weaving traditions, animistic

religious beliefs, and clan-based social structures laid the groundwork for the

region’s indigenous character.

The Rise of Kamarupa: Indo-Aryan Influence and Political Consolidation

By the early centuries CE, the ancient kingdom of Kamarupa emerged

as a powerful political entity in the Brahmaputra Valley.

References in the Mahabharata and Puranic texts describe

Pragjyotisha-Kamarupa as a distant eastern kingdom. Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang,

who visited in the 7th century, recorded a flourishing polity under King

Bhaskaravarman.

During this period, Indo-Aryan linguistic and cultural

influences intensified. Assamese gradually evolved from eastern Indo-Aryan

Prakrits, absorbing local Tibeto-Burman phonetic and grammatical features. The

Sanskritic tradition coexisted with indigenous belief systems.

The iconic Kamakhya Temple symbolizes this synthesis,

blending Tantric Hinduism with earlier fertility cults and tribal rituals.

The Tai-Ahom Arrival: A Six-Century Transformation

A defining moment in Assamese history came in 1228 CE when Sukaphaa

crossed the Patkai hills and established the Ahom kingdom.

Initially Tai-speaking and practicing their indigenous

religion, the Ahoms gradually assimilated into the broader Assamese society

through a long process of political adaptation and cultural exchange. Over

nearly six centuries of rule (1228–1826), they built a structured

administrative system known as the Paik system, which

organized adult males into service units for military and civil duties. This

system ensured efficient governance and resource management across the

kingdom.The Ahoms also strengthened military organization, developing

river-based warfare strategies that proved decisive during conflicts with the

Mughals.

Over time, the Ahoms adopted the Assamese language for

administration and court proceedings, and many later Ahom kings embraced

Vaishnavite Hinduism. Royal patronage of Vaishnavite institutions and

participation in Hindu rituals further deepened their cultural integration.

This gradual assimilation transformed the Ahoms from a Tai ruling elite into a

central pillar of Assamese identity and state formation.

The Ahom polity was not ethnically exclusive. It incorporated

local chiefs, Bodo-Kachari groups, and various tribal communities into

governance structures. Over time, the Ahoms themselves became culturally

Assamese.

Their legacy includes architectural marvels such as Rang Ghar

and Talatal Ghar, and a political structure that fostered territorial unity.

The Bhakti Movement: Cultural Unification

In the 15th–16th centuries, Srimanta Sankardev launched

the Neo-Vaishnavite movement (Ekasarana Dharma).

This reform movement transcended caste and ethnic divisions,

emphasizing devotion, equality, and community participation. Institutions such

as Sattras and Namghars became social hubs that unified diverse communities.

Cultural forms like Borgeet,

Bhaona, and Sattriya dance fostered a shared artistic identity. The movement

acted as a powerful integrative force, helping transform a multi-ethnic region

into a culturally cohesive society.

Rise of the Koch Kingdom (16th Century)

The Koch are generally considered to be of Tibeto-Burman origin, closely

linked to the larger Bodo-Kachari ethnic family.

The political rise of the Koch began in the early 16th century

under Biswa Singha, who united scattered tribal chiefs and founded the

Koch dynasty. Under his son Naranarayan, the kingdom expanded

significantly, while his brother Chilarai led successful military

campaigns across Assam and neighboring regions, making the Koch Kingdom one of

the most powerful states in Northeast India.

Understanding the Koch is essential to understanding how Assam evolved from

scattered tribal polities into a region defined by territorial unity and

cultural synthesis.

Understanding the Koch is essential to understanding how Assam evolved from scattered tribal polities into a region defined by territorial unity and cultural synthesis.

Colonial Rule and the Emergence of Modern Assamese Identity

The Treaty of Yandabo (1826), signed after the First Anglo-Burmese War, formally ended nearly six centuries of Ahom rule and brought Assam under British administration. This marked a turning point in the region’s political, economic, and social history.

Under colonial rule, Assam’s economy and demography were

significantly reshaped:

Expansion of Tea Plantations:

The

British discovered the commercial potential of Assam tea in the 1830s. Large

tracts of land were cleared for plantations, particularly in Upper Assam. Tea

soon became a major export commodity, integrating Assam into the global

capitalist economy.

Migration of Laborers from Central India:

To meet the labor demands of the tea industry,

the British brought thousands of workers from present-day Jharkhand, Odisha,

Chhattisgarh, and Bihar. These communities, often referred to as Tea Tribes or

Adivasis, permanently altered Assam’s demographic composition.

Arrival of Bengali Administrators and Clerks:

Since the British initially administered Assam

as part of the Bengal Presidency, Bengali officials, teachers, and clerks were

appointed to administrative and educational positions. In 1836, Bengali was

made the official language of administration, which later triggered resistance

and the Assamese language revival movement.

Integration into Global Markets:

Assam’s

economy shifted from a largely agrarian and localized system to a

plantation-based export economy. Tea, oil (discovered in Digboi in the late

19th century), and timber became key commodities linked to global trade

networks.

In 1836, Bengali was imposed as the official language. The

resistance to this decision sparked a linguistic revival, restoring Assamese in

1873. This episode played a critical role in forging modern Assamese

nationalism.

Assamese identity began to crystallize around language,

literature, and regional pride.

The British discovered the commercial potential of Assam tea in the 1830s. Large tracts of land were cleared for plantations, particularly in Upper Assam. Tea soon became a major export commodity, integrating Assam into the global capitalist economy.

To meet the labor demands of the tea industry, the British brought thousands of workers from present-day Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Bihar. These communities, often referred to as Tea Tribes or Adivasis, permanently altered Assam’s demographic composition.

Since the British initially administered Assam as part of the Bengal Presidency, Bengali officials, teachers, and clerks were appointed to administrative and educational positions. In 1836, Bengali was made the official language of administration, which later triggered resistance and the Assamese language revival movement.

Assam’s economy shifted from a largely agrarian and localized system to a plantation-based export economy. Tea, oil (discovered in Digboi in the late 19th century), and timber became key commodities linked to global trade networks.

Who Are the Assamese?

The Assamese people are not a single ethnic group but the

product of centuries of cultural interaction and historical evolution. They are

descendants of early Tibeto-Burman tribes who formed the indigenous foundation

of the Brahmaputra Valley. Over time, they were influenced by Indo-Aryan

settlers whose language and religious traditions shaped the region’s linguistic

and cultural framework. Their political identity was further strengthened by

Tai-Ahom statecraft, which consolidated territorial unity for nearly six

centuries. The Neo-Vaishnavite reform movement provided a powerful cultural and

spiritual bond that unified diverse communities under a shared social ethos.

Later, colonial-era migrations introduced new demographic and economic

dimensions, further contributing to the composite character of Assamese

society.

Their language belongs to the Indo-Aryan family but bears

Tibeto-Burman imprints. Their religious practices blend tribal traditions with

Hindu philosophy. Their social structure reflects centuries of assimilation.

Assamese identity evolved not through racial purity, but through

cultural negotiation.

A Civilization of Synthesis

The origins of the Assamese people illustrate how identities are

formed through convergence rather than exclusion. From Neolithic settlers to

Ahom kings, from Vaishnavite reformers to colonial-era intellectuals, each

layer contributed to the making of Assamese civilization.

Assam’s history is not a tale of isolation; it is a testament to

adaptation, resilience, and synthesis. The Assamese people emerged from

diversity and continue to embody it.

In understanding their origins, we understand not only Assam’s

past, but the enduring power of cultural coexistence.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Critical Script or its editor.

Newsletter!!!

Subscribe to our weekly Newsletter and stay tuned.

Related Comments